Do You Need a Ph.D.?

Whether you need—or should get—a Ph.D. ultimately depends on why you’re doing it, and if you’re doing it for the right reasons.

Whether you need—or should get—a Ph.D. ultimately depends on why you’re doing it, and if you’re doing it for the right reasons.

Nobody “Needs” a Ph.D.

I recently saw a social media post that claimed “you don’t need a Ph.D.” Of course you don’t need a Ph.D. To claim that you don’t need a Ph.D. is completely besides the point. Here was my reply to that post:

You also don’t “need” to climb Everest, yet some people find that a worthwhile experience. A Ph.D. is about the journey, the experience of growth, learning, contributing to knowledge, deep expertise. Not for everyone, but for many it is incredibly rewarding.

My response I think sums up the value of a Ph.D. in a nutshell: Nobody needs a Ph.D. For you, it might still be the right answer. For many, it is the most fulfilling experience of their lives. For others, it can be a frustrating path. Whether the path makes sense for you depends on your goals. One thing is certainly true: You have to want it as part of your own personal life plan, for the right reasons—not for any other reason, and certainly not for anyone else.

The Fire Must Come From Within

Intrinsic motivation is key. It is somewhat easy to get hung up about titles—many people seem to want to tack the phrase “Ph.D.” to the end of their name as a way to somehow signal credibility of authority. But a Ph.D. is neither necessary nor sufficient for succeeding in life, or even being a valuable contributor to a team.

A Ph.D. is a long road and ultimately a personal, solo journey. The motivation has to come from within; success comes as a result of putting one foot in front of the other, consistently, over and over again.

A Ph.D. is a long road and ultimately a personal, solo journey. The motivation has to come from within; success comes as a result of putting one foot in front of the other, consistently, over and over again.

It can and often is an incredibly valuable and life changing experience, but in order to succeed, you have to be doing it for the right reasons, which essentially boil down to intrinsic motivation, as opposed to a quest for some external validation. This is, of course, true for many things in life, but the Ph.D. is a long, multi-year journey, with challenges and ups and downs. To succeed (and to enjoy the experience), you need to be pursuing the degree for the right reasons, based on internally motivating factors.

**Trust the process. **The benefits of a Ph.D. ultimately derive from the process of obtaining the degree, and not from the degree itself. While it is true of many things in life, for the Ph.D. especially, the journey of personal discovery and growth along the path to the degree is as edifying as the milestone of obtaining the degree itself.

Why Get a Ph.D.?

I think there are four main—and orthogonal—reasons that you may want to get a Ph.D.:

**Discovery. **You want to contribute to the body of existing knowledge by making new discoveries.

**Expertise. **You want to gain deep expertise on a particular subject matter, or (as is increasingly necessary) across a range of subject matters.

**Transferrable Skills. **You want to gain a wide range of transferrable skills in problem solving, critical thinking, and communication.

**Autonomy. **You want to develop the ability to work independently, on problems of your choosing.

Note some things that are missing from this list: Impressing your friends and family, securing a particular job, following someone else’s plan for your life, pursuit as a “meanwhile” activity, and so forth are conspicuously absent here. Any of these reasons might have some merit—in particular, certain jobs, such as being a tenure-track university professor—do require the credential.

The point is that if that is your main reason for wanting to pursuit the degree, you will not ultimately find fulfillment in the pursuit. Along the way, you will face setbacks, discouragement, self-doubt, impostor syndrome, and a lot of obstacles that you cannot foresee. As I mentioned above, overcoming these obstacles and doubts ultimately requires some intrinsic motivation and reasons for your pursuit. I’ll now expand on the three I mention above.

The Joy of Discovery

A journey towards a Ph.D. is fundamentally one of knowledge creation. As part of your Ph.D., you have a chance to work on a problem that nobody has ever worked on before. The answers are certainly not in any textbook (if they are, you’re working on the wrong problem!), and in many cases, the problem itself may not even be written down or formalized anywhere. John Dewey said, “A problem well-put is half solved.” In practical terms for your Ph.D.

You are working at the frontier of human knowledge and understanding and trying to bump that frontier just a little bit further out.

The process of creating knowledge can be lonely and frightening, but many people find it very exciting. When you embark on a new project, you often have no idea what you will find, or whether what you are doing will even work. The only thing you can be reasonably sure of is that you will learn something.

At the University of Chicago, my lab studies how network traffic can enable powerful statistical inference, from network security and privacy to human behavior.

At the University of Chicago, my lab studies how network traffic can enable powerful statistical inference, from network security and privacy to human behavior.

If that sounds exciting to you, you will probably enjoy the Ph.D. If working outside the lines without someone telling you what to do and without a clear path to a known end goal makes you uncomfortable, you may find that the Ph.D. is not for you.

Deep Expertise and Broad Awareness

Another reason to pursue a Ph.D. is a desire to understand a particular topic more deeply. You may have been fascinated by a particular topic in your undergraduate coursework (or otherwise), and a Ph.D. is an opportunity to dive deep into a particular facet of that subject matter. For example, in computer science, undergraduates may take a single course in computer networking, operating systems, or security, where the topic is covered at a fairly high level.

While it may seem less obvious initially, a Ph.D. is also an opportunity to gain a little bit of knowledge about a lot of different areas. This oft-forgotten aspect of the Ph.D. is often the key to success, because making connections that others cannot see is often what enables a creative solution or breakthrough—but the ability to make those connections requires being able to know what dots exist, so that you can connect them when opportunities arise.

**Deep Expertise: Knowing a lot about a little. **A Ph.D. provides the opportunity not only to deepen knowledge in a particular sub-area, but also to explore the frontiers of knowledge in that particular area. Ultimately, the goal of the Ph.D. is to create new knowledge in a particular area, and achieving that successfully typically requires a deep understanding of the frontiers of knowledge in that area. As part of the process of discovery, as a Ph.D. student you gain mastery of a particular topic area. Developing this mastery often takes years, because it requires becoming an expert within a discipline, understanding not only the frontiers of knowledge and capabilities, but also what others have attempted (successfully and unsuccessfully) to advance this frontier.

**Broad Awareness: Knowing a little about a lot. **When most people think of a Ph.D., they think of deep subject matter expertise. But, increasingly in modern times, a Ph.D. requires not only hyper-specialization but also breadth, of what David Epstein calls “Range”. Essentially, range is the ability to approach and solve problems that are not always cleanly formulated or articulated—the so-called “messy world” problems, as opposed to “kind world” problems. Epstein brings up examples such as golf and chess as anomalies—these are skills and problem areas where the problem space is well-defined, and repetitive practice leads to mastery. But as it turns out, most problems in this world—and especially those that you will encounter and define in your Ph.D.—are not the type where the solution is known, clean, and simply achieved by repetitive practice. Typically, a solution or breakthrough will require thinking differently from everyone else has about the problem. This is increasingly true as knowledge advances and our fields mature, since so many people—including plenty of people without a Ph.D.!—are thinking about solutions to new problems that arise every day. One of the advantages that a Ph.D. provides is the ability to gain knowledge about a lot of different areas, as well. In other words, you have the chance to know a little about a lot—through courses, interactions with students and colleagues across disciplines, and so forth. Knowing a little about a lot of areas is invaluable in making connections.

Transferrable Skills

Most people who get a Ph.D. do not become tenured university professors; many Ph.D.s leave academic research altogether. While I myself have been fortunate to have past and ongoing success as an academic researcher—and also to have had the pleasure of seeing many of my students do the same!—many of my peers and my own students have left academic research for industry, either immediately after the Ph.D., or eventually.

I have seen many people think or declare that a Ph.D. is “wasted” if it does not result in a prosperous career as an academic. Nothing could be further from the truth, as many of my students have later told me. I am often reminded of one of my former students telling me about his time at a large software company where he has been repeatedly asked to prepare presentations, present his group’s work to his team, and so forth. His peers were mystified by his skills: “Where did you learn to do this?” they asked him. His reply: During my Ph.D. I think my student’s exchange perfectly sums up the notion that a Ph.D. affords more lessons than simply those in the technical domain. It also allows you develop a number of skills that transcend your chosen discipline. Specifically, a Ph.D. offers many of the following transferrable skills:

**Putting structure around an ambiguous problem. **Undergraduate education primarily consists of fixed, well-formulated problems and topics. Assignments come in the form of problem sets; assessments come in the form of exams. A Ph.D. is essentially the diametric opposite: A significant portion of the work involves imbuing structure into a problem that is ambiguous, taking a problem statement that is vague and sometimes ill-formed (or not formed) and breaking the problem down into solvable pieces. This is a skill that will serve you well regardless of whether you pursue a career in academic research; as David Epstein points out in Range, most of the problems in the world are not “kind” problems—you will very likely need the skills to tackle the messy ones.

**Working around obstacles and reframing a problem. **On a related note, because the problems you will encounter and address as part of pursuing a Ph.D. have (by definition) not been solved before, at some point during the process you may discover that the problem you have formulated isn’t solvable. Often, it is necessary to reframe a problem, or pivot entirely to a problem that can be solved. When tackling research, I repeatedly ask whether the data we are gathering points to the need to take a different approach, or to explore different hypotheses. Again, this ability to “pivot” a problem-in-progress, based on experience and learning, is a skill that transfers to many aspects of life.

**Critical thinking and “data literacy”. **Much of a Ph.D. involves reading other people’s research to determine the current state of knowledge. Part of this process involves critically evaluating claims made in published literature. Often, a fresh Ph.D. student might read the title or abstract of a paper and assume that the entire field has been “solved”. A closer read, however, often points to many open doors and opportunities for future research. On a related note, papers can sometimes overstate conclusions, and learning how to critically evaluate the claims of a publication against the evidence is an increasingly important skill in today’s society. In The Art of Statistics*, *David Spiegelhalter talks about many ways to assess the veracity of claims based on data-driven experiments. Among them, he notes the use of **relative effects **instead of absolute ones, as a common way that results and findings can be overstated (e.g., for a absolute quantity like 10, a difference in one data point is 10%, even though the absolute effect may be minimal or negligible). Paying attention to experiment design, noting what results are actually significant, attempting to reproduce and rationalize results, are all part of the process one goes through as part of a Ph.D.—and these skills are certainly increasingly important in today’s world where “data literacy” is paramount.

**Verbal and visual communication. **A significant portion of research is in fact communicating the results of the research—to colleagues (with journal and conference publications, talks, etc.), to the general public (e.g., via communication with journalists). A clear, compelling—and precise—narrative for the problem statement and results is often as important as the research itself. This part of the process often involves a significant process of distilling results to their essence. While there can sometimes be a desire to communicate every detail, and the chronology of the research process (a significant portion of the time may have been spent exploring dead ends!), the researcher’s job is ultimately to communicate the importance of the problem being studied, the main takeaways from the work, and the support for those results and conclusions. Details in talks can and should be left to papers; the papers themselves, however, can and should be precise, clear, and detailed enough to allow a reader both to understand the significance of the result and (if desired) attempt to replicate it (possibly with independent data, if the original dataset is not publicly available).

**Teaching. **Most Ph.D. students will teach in some form, usually as a teaching assistant for a course taught by a professor. A teaching assistant’s job can vary, but the best ones are those that give the student experience teaching in a classroom in front of students, direct interactions with students (e.g., through office hours), and the opportunity to craft assignments. The worst teaching assistantships are those that involve mostly grading—I try to make sure my own students avoid TAships that are primarily grading, and instead are those that involve actual teaching experience. The experience of teaching is valuable, even if you never intend to become an instructor or university professor. In essence, all of us are teaching each other every day—teaching typically involves the process of taking a complex topic, breaking it down, and presenting and explaining it in terms that a student (or group of students) can understand. This process of conveying a complex topic in simple, understandable terms is again a valuable skill across many professions.

**Working independently and consistently. **As mentioned above, much of the Ph.D. is unstructured work—you set your own schedule, making progress towards a goal that is sometimes years into the future. Achieving such a goal requires developing habits for working consistently and independently, which, again, is a skill that just about all of us can benefit from developing. Most success in life comes not from being consistently great, but rather from being great at being consistent.

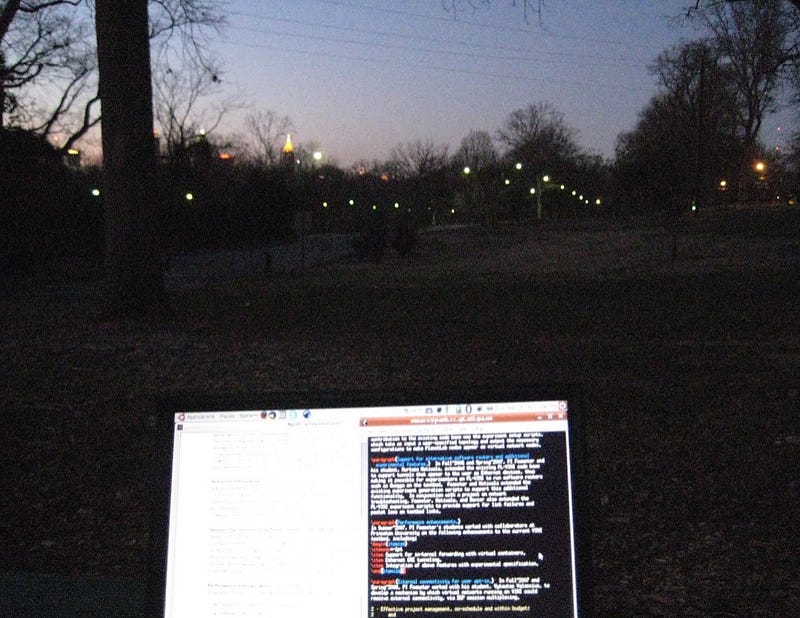

Research and Ph.D. work can involve late nights, but not all of them need be in windowless offices. In fact, the work often affords significant flexibility for when and how you choose to work. Disicpline and consistency are key but can yield significant freedom and autonomy.

Research and Ph.D. work can involve late nights, but not all of them need be in windowless offices. In fact, the work often affords significant flexibility for when and how you choose to work. Disicpline and consistency are key but can yield significant freedom and autonomy.

Autonomy

The autonomy that a life in research brings and the ability to work at the limits of your own creativity and ambition are rare privileges that many people do not enjoy in life.

Throughout life, you will meet many people who are unhappy in their jobs. I can honestly say that I have never dreaded a day of work, and even though professors work very hard, you will be hard-pressed to find a professor who does not like his or her job. I’m not sure I’ve met one. I believe the reason for this is that we have jobs that never get boring, and if we are bored, we really have only ourselves to blame, since we can work on whatever we choose. Being a professor carries certain perks over being a postdoc (e.g., more cachet, more autonomy, more pay), but it also brings with it more responsibility, more committees, and more work that can distract from research. Despite the fact that professors often have three or more jobs (e.g., teaching, research, committees, and other service work), we are generally a very happy bunch.

When I was a graduate student, I always thought that I had the best job in the world (the pay notwithstanding). Perhaps being a postdoc is the best job in the world, because it has all of the perks of being a Ph.D. student, with considerably better pay. As a graduate student (or postdoc), you have a unique opportunity to work on whatever problems you find interesting. And, unlike a professor, a postdoc affords the opportunity to work on only one or two things at once and dive deep into those problems.

A Ph.D. can be a great adventure, and a time to make friends, too. Here I am on a bike ride in Atlanta with my research group at Georgia Tech back in March 2008. The bonds you form with other Ph.D. students can be life-long.

A Ph.D. can be a great adventure, and a time to make friends, too. Here I am on a bike ride in Atlanta with my research group at Georgia Tech back in March 2008. The bonds you form with other Ph.D. students can be life-long.

Bad Reasons to Get a Ph.D.

Some of the claims that you don’t “need” a Ph.D.—such as the post on social media that inspired my reply at the beginning of this article—typically presume that you are setting out to get a Ph.D. for the wrong reasons in the first place. If you are thinking of pursuing the Ph.D. as a means to an end—status, money, a particular job—then you are likely to find that the Ph.D. is not only unnecessary, but possibly also unrewarding. If you’re not viewing the Ph.D. itself as a journey and as part of the process of growth, you’re very likely doing it wrong. If any of the reasons below are your primary reason for getting a Ph.D., you may be setting yourself up for disappointment.

Financial or Career Status

Obtaining the Ph.D. presents a serious financial opportunity cost. For five (or more) years, you will be making about 20% of what your peers are making in industry out of college. Furthermore, you will miss out of five years of raises and promotions on top of that higher salary that you could have been already making. Ultimately, fifteen or twenty years later, you might close this gap, when you become a tenured professor and consulting and startup opportunities present themselves in abundance (should you decide that you want to spend your time on that). Until then, unless you happen to be one of the fortunate few whose Ph.D. leads to the next breakthrough startup, you should plan on being financially set back from your friends and acquaintances who are in industry. That is not to say that you will experience those setbacks, but if your goal is to become wealthy quickly, a Ph.D. is probably not the right career path for you.

A Chance to Take More Classes

Some people enter the Ph.D. program as a chance to take more classes. I have heard of cases of students getting bachelor’s degrees in other areas while completing their Ph.D. in computer science. This is ridiculous; it is not what you come for, and if your advisor finds out you are doing this, he or she will likely not be pleased. If you want to take more classes and get another degree, you should just go do that. The research will be a distraction from your main goal. I tend to encourage my students to complete their coursework as quickly as possible so that they can focus on research.

As a Default or Meanwhile Option

If you enter a Ph.D. program simply because you do not like the “real world” or the thought of having a “real job”, or because you liked school but can’t figure out what you’d like to do with your life, you will almost certainly strongly dislike your Ph.D. experience, and you will probably not succeed. A Ph.D. is not well defined. There are no assignments and checklists. There is no “homework” in the traditional sense. Although you have an advisor whose job it is to guide you along your path, the path you take in your Ph.D. is ultimately deeply personal, and it is driven by your passions and interests (or lack thereof). If you do not have a strong passion or the initiative to carry through your Ph.D. to completion, you will find the process to be very painful. Your success (or failure) ultimately rests on your shoulders.

The Choice is Personal

Obtaining a Ph.D. is a deeply personal experience. Your advisor will make sure that you are making progress (if he or she is doing the job well), but ultimately it is up to you to shape your experience.

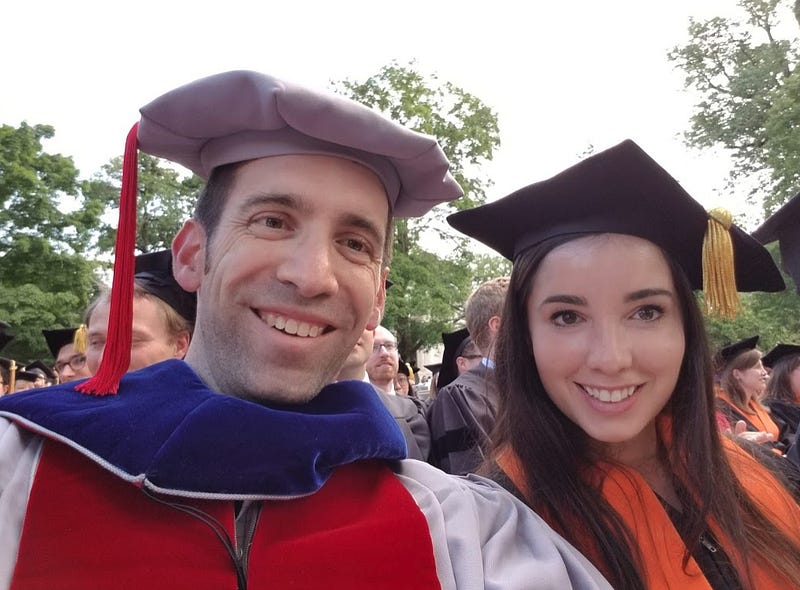

Graduating from a Ph.D. is always a proud moment. Here I am with one of my Ph.D. students at Princeton’s commencement.

Graduating from a Ph.D. is always a proud moment. Here I am with one of my Ph.D. students at Princeton’s commencement.

To do well in the Ph.D. program, you need the passion for creating new knowledge and the tenacity to push your visions through to conclusions when the going gets tough. Many people love the Ph.D. process. For me, it was one of the best experiences in my life, and it has certainly shaped everything I’ve done going forward. I would recommend it to anyone who shares many of the same attributes and goals that I have.

But, it’s also important to realize that the Ph.D. is not for everyone. It might even take you some time and experience going through the process to realize that the Ph.D. is not for you; that is also perfectly alright. There is absolutely no stigma in avoiding further sunk costs; at any time, you should be setting yourself on a path that gives you the best opportunities for success and happiness. I hope these thoughts have helped you determine whether the Ph.D. is that path for you, but ultimately, it is difficult to know for sure until you have been through (or at least tried) the process yourself.

By Nick Feamster on August 31, 2020.

Exported from Medium on October 28, 2025.